Healing Trauma and Strengthening Attachment: What We Learned from Our Pilot Study

We’re at the United World Conference for the American Association of Christian Counselors this week, sharing the results of our pilot study!

When we first dreamed of offering a trauma-focused group therapy experience that combined both evidence-based clinical treatment and spiritual direction, we weren’t sure what the outcome would be.

Could Christian college students really find healing in a group that honored both their mental health needs and their faith, in light of carrying trauma and relational wounds?

In January 2024, with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Fuller Theological Seminary and Vanguard University, and with participant compensation support funded by Travis Research Institute, we launched a 13-week pilot study. And, what unfolded was both deeply personal and statistically significant.

Hence, we’ve been approved to continue offering the group therapy as a study, as we build on the pilot results below with more students in California.

What We Did Together

Six Christian college students, each carrying trauma from their past, joined us for a weekly 1.5-hour group.

To participate, they needed at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) and some clinical or subclinical symptoms of PTSD or complex PTSD.

The group was co-led by master’s-level therapists trained in spiritually integrative care and a spiritual director. Students engaged in:

Psychoeducation on trauma and attachment

Trauma narrative processing and group support

Inner healing prayer and artistic spiritually directive practices

Optional journaling and at-home exercises

Alongside compensation, students often described participation as “a divine appointment” or a “lifeline” amidst personal crises.

What the Numbers Told Us

We tracked students’ symptoms at the beginning with a pre-test, midpoint, and at the end of the 13-weeks post-test. Here’s what stood out:

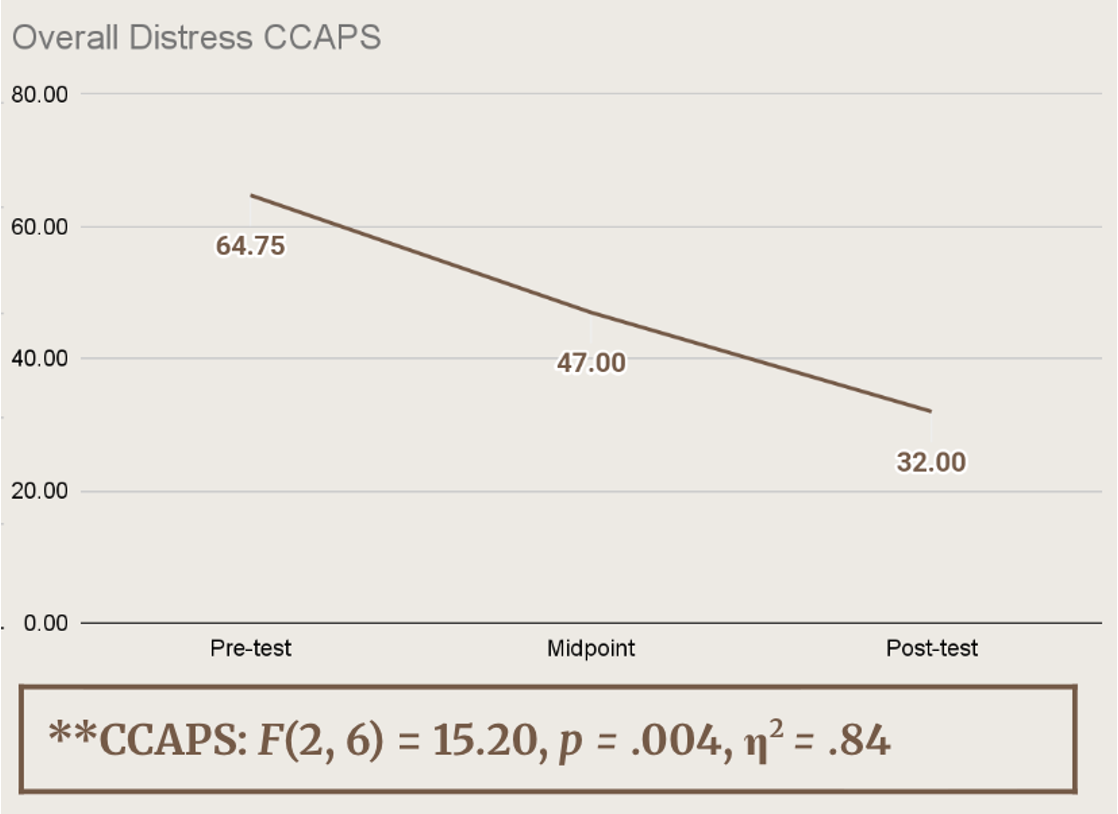

Overall distress dropped dramatically

Statistically significant: F(2,6) = 15.20, p = .004, η² = .84

Meaning: Students left the group feeling far less overwhelmed and distressed by life.

Their overall distress, as measured by the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62; Locke et al., 2011), which is widely used across college and university counseling centers, decreased significantly across the group. The chances this was random are less than half a percent, and the size of the effect was very large. So, the group explained much of the changes we saw.

Key Specific Symptom Findings:

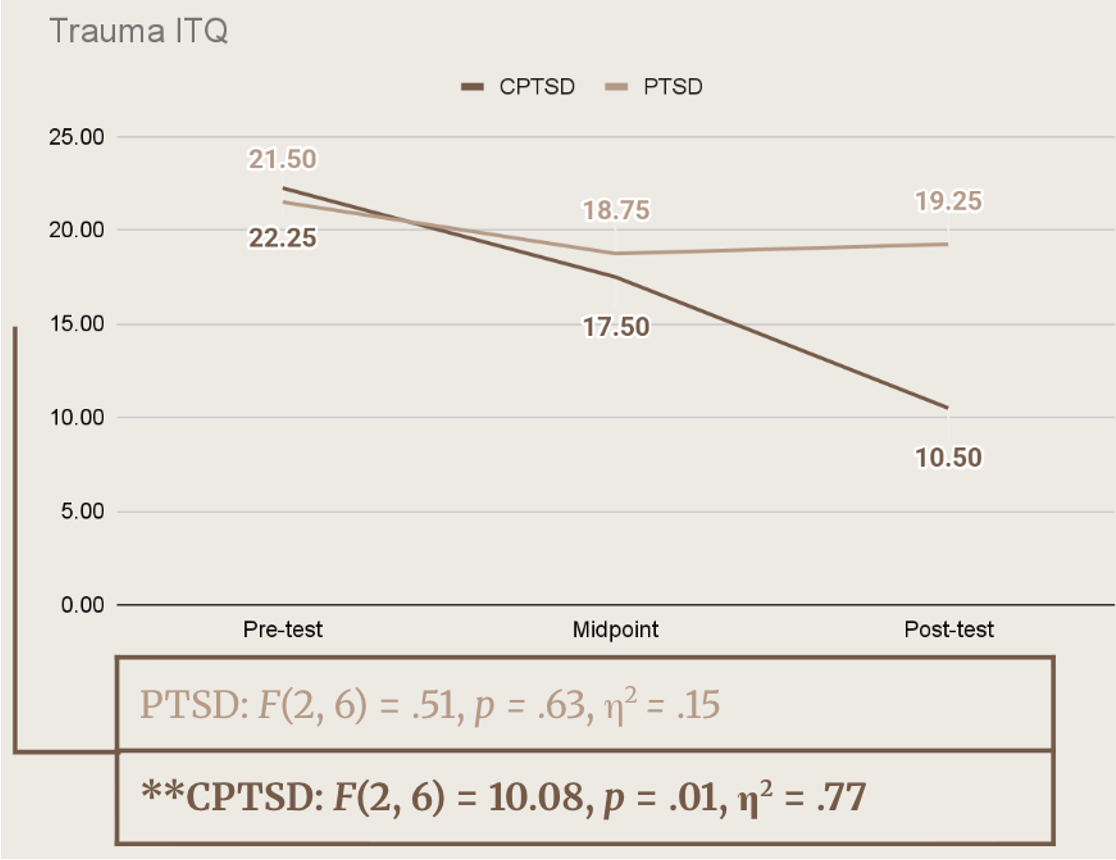

Statistically significant CPTSD symptoms showed one of the largest changes (F = 10.08, p = .01, η² = .77)

Meaning: Trauma symptoms (like intrusive memories, emotional numbness, and hypervigilance) significantly decreased. The group made a big impact here as well.

Interestingly, while we saw very strong decreases in symptoms of complex PTSD, scores for classic PTSD symptoms, according to the International Trauma Questionnaire (Cloitre et al., 2018) didn’t show the same statistically significant drop.

With such a small group of students, each person’s journey powerfully shaped the averages. For example, one participant who went through a major crisis during the second half of the study, who had elevated scores given the recent scare, may have pulled the overall PTSD numbers higher at post-test.

What this tells us is not that the group isn’t helpful for PTSD, but rather that we need a larger sample size to truly see the pattern. In fact, since other measures, like overall distress and complex PTSD, decreased very significantly, we see evidence of an overall impact of the group. With more students, we expect to get a clearer picture of how the group supports recovery from both classic PTSD and complex PTSD.

Statistically significant Frustration and Anger decreases (F = 7.37, p = .02, η² = .71)

Meaning: Students were better able to regulate anger more at post-test. They reported less escalation from frustration to anger over time.

Statistically significant Academic distress — feeling weighed down by school — fell strongly (F = 8.05, p = .02, η² = .73)

Meaning: Stress and difficulty with school responsibilities improved significantly. Students felt more capable of handling academic demands.

Marginally significant Depression decreases (F = 4.46, p < .10, η² = .60)

Meaning: Students’ depressive symptoms went down. The trend was strong and meaningful, though in statistics it’s considered “marginally significant.” In cases like this, more participants would offer visibility into if this pattern continues with more impact.

Marginally significant Family Distress decreases (F = 3.37, p < .10, η² = .53)

Meaning: Family-related stress decreased. Again, this was a strong trend, though technically considered “marginally significant,” requiring more participants for more clarity.

Noticeable Substance Use decreases (F = 3.14, p = .12, η² = .51)

Meaning: Students reported less substance use, and although this wasn’t “statistically significant” with such a small sample, the effect size suggests meaningful movement. Hence, further necessitating more study with more participants to see if the trend holds.

Noticeable Eating decreases (F = 2.71, p = .15, η² = .48)

Meaning: Students reported fewer eating concerns, potentially leading to less disordered eating, and similar to substance use, showed encouraging signs of improvement and potential for trends to become clearer with more students in our future groups.

Because trauma often affects coping behaviors like eating and substance use, even these small shifts matter, and we’re eager to see whether they strengthen with more student groups.

Attachment Changes to Others and God

One of the most powerful shifts was relational and spiritual with significant shifts in attachment.

Attachment refers to the way we form emotional bonds and expectations of safety with others. Psychologists describe four main attachment patterns based on two dimensions — anxiety (fear of abandonment) and avoidance (fear of closeness):

Secure: trusting, able to balance closeness and independence.

Preoccupied/Anxious: high anxiety, low avoidance — craving closeness but fearing rejection and abandonment.

Dismissive/Avoidant: low anxiety, high avoidance — valuing independence but struggling with closeness.

Fearful/Disorganized: high in both anxiety and avoidance — both fearing abandonment and fearing closeness.

Trauma often disrupts healthy attachment development, leaving survivors struggling to trust others (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, 2000; Lahousen et al., 2019; Lim et al., 2020; Toof et al., 2020). For people of faith, this means trauma can deeply affect both human relationships and spiritual ones. Research shows insecure attachment after trauma can worsen distress (Massengale et al., 2017; Zeligman et al., 2020).

Healing often involves intentional movement toward earned secure attachment, where trust and safety can be re-learned.

Key Attachment Findings

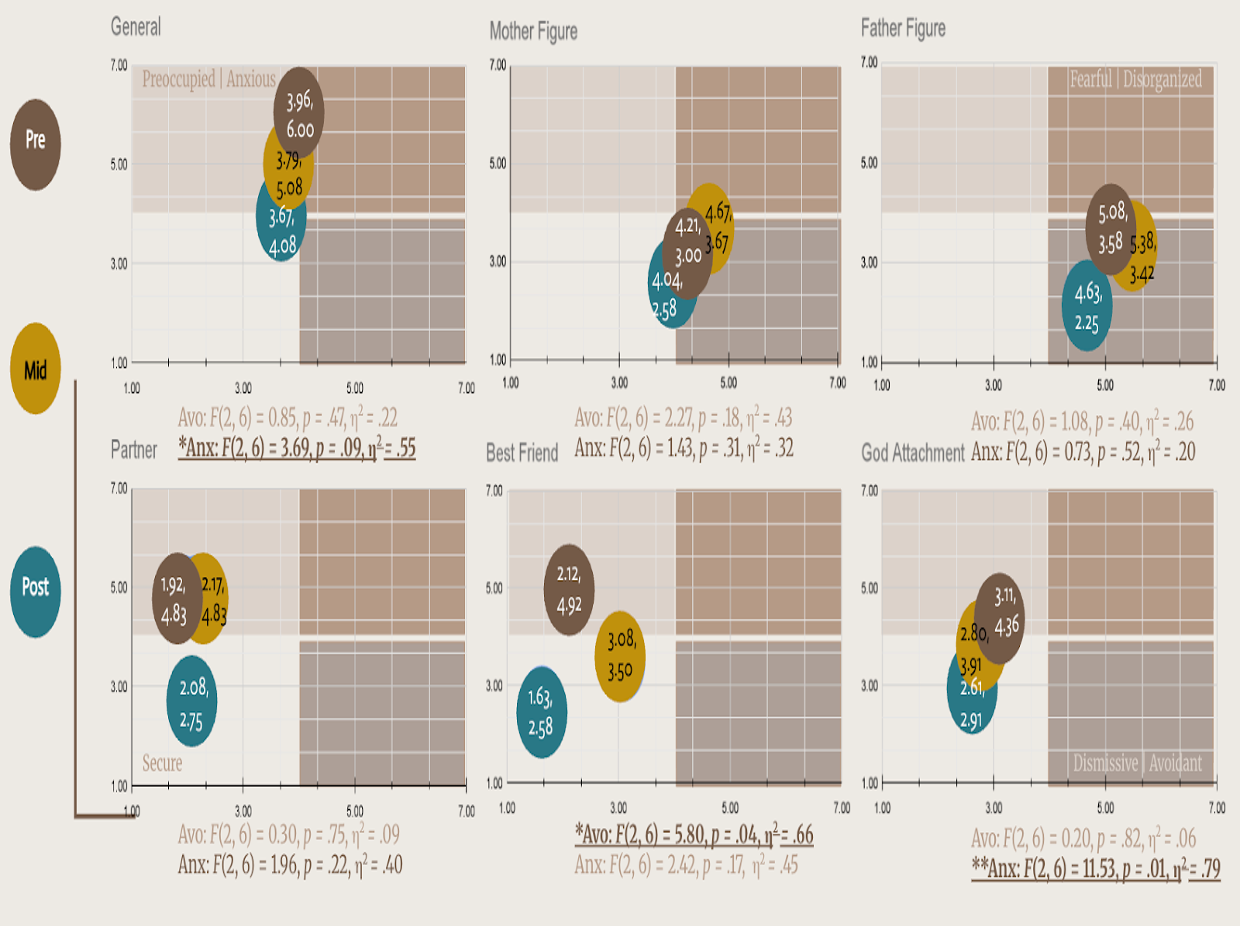

In our group, attachment shifts were most noticeable in two key areas:

God Attachment:

Anxiety toward God dropped significantly (F = 11.53, p = .01, η² = .79).

Meaning: Students felt more secure in trusting God’s presence and dependability in their vulnerability with less anxiety, according to the Attachment to God Inventory (Beck & McDonald, 2004). Additionally, avoidance toward God trended downward.

Best Friend Attachment:

Avoidance decreased significantly (F = 5.80, p = .04, η² = .66).

Meaning: Students became more willing to lean on close peers rather than pull away according to their scores on the Experiences in Close Relationships - Relational Structures (Fraley et al., 2011). Additionally, their anxiety towards their best friends trended downward.

General Attachment (overall pattern across relationships):

Anxiety showed a marginal decrease (F = 3.69, p = .09, η² = .55).

Meaning: This suggests a promising trend toward greater relational security in broad social contexts, especially as their avoidance also trended downward.

Other attachment categories (e.g., mother, father, partner) illustrated directional trends toward earned secure attachment, but more participants are required to see if such trends reach statistical significance in the future.

Shifts from attachment anxiety and avoidance to secure attachment (green lower left corner).

Religious and Spiritual Struggles

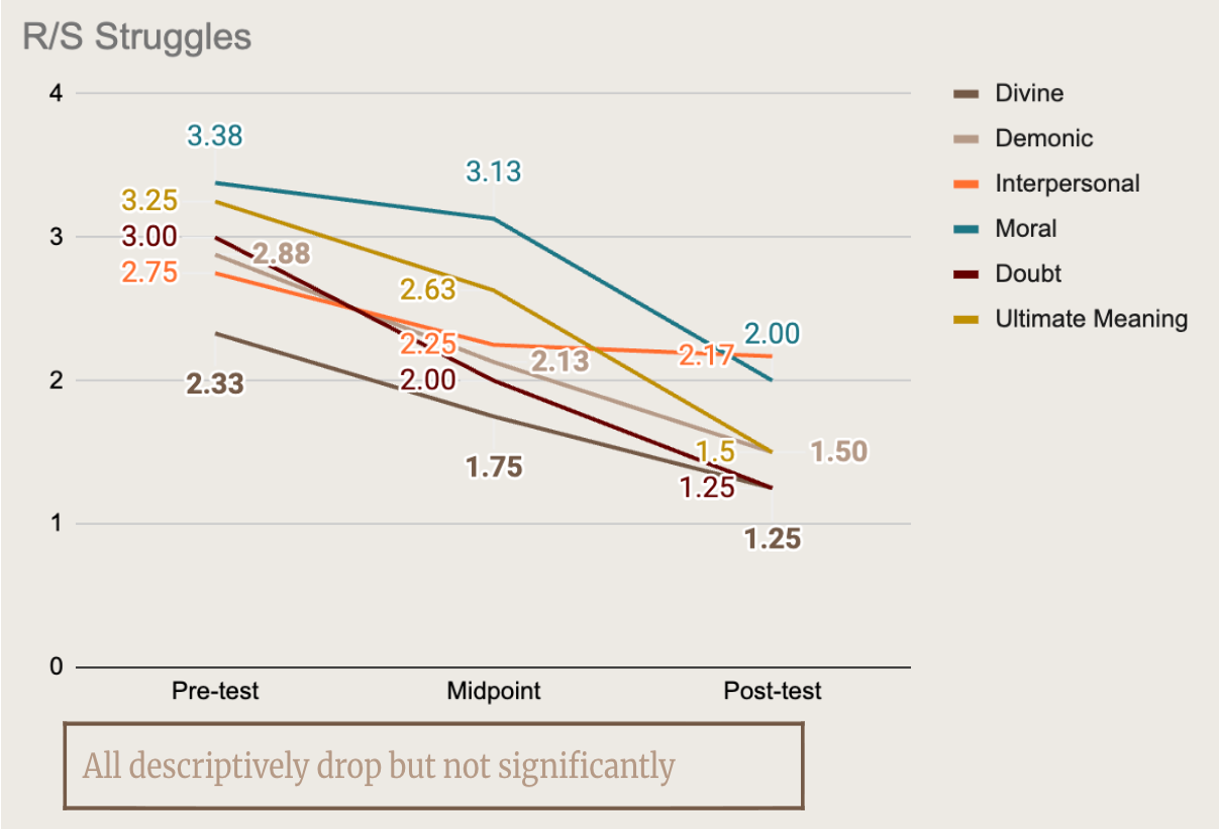

Alongside shifts in attachment, we also measured students’ religious and spiritual struggles (RSSS-14; Exline et al., 2022). These struggles can include doubts about God, feelings of ultimate meaninglessness, interpersonal spiritual conflicts, or moral and demonic struggles. Trauma survivors often carry these spiritual wounds quietly, unsure if they’re “allowed” in spaces of faith.

In our group, all six categories of struggles descriptively dropped from pre- to post-test — including doubt, meaning, moral, interpersonal, demonic, and divine struggles. While these decreases did not reach statistical significance in such a small sample, the downward trend is encouraging:

Moral struggles dropped the most (3.38 → 2.00).

Doubt and divine struggles each decreased by about a full point.

Even ultimate meaning struggles showed steady decline (3.25 → 1.50).

👉 Meaning: Students reported wrestling less with doubt, guilt, or questions of meaning by the end of the group. Though we can’t say with statistical confidence yet, these early patterns suggest the group may have helped students reconcile their faith and trauma in a healthier, more hopeful way.

Diversity in Experience

We also noticed important correlational differences based on background:

Hispanic/Latinx students found the educational readings especially valuable (p = .04).

Catholic and Lutheran students considered trauma narrative processing more spiritually meaningful compared to Pentecostal/Nondenominational peers (p = <.01).

Denominational background influenced how students connected with God-attachment measures.

👉 This reminds us: Healing is never one-size-fits-all! Culture and faith traditions shape how people experience care.

Students in Their Own Words

Statistics only tell part of the story. Here’s how participants described the experience:

“I feel and see growth in myself after being part of this pilot study… I really believe it was a divine appointment, in every session. I loved the experience and would gladly recommend it to others.” — Participant 1

“Spiritual wounds cause such pain to people, and rarely are they ever addressed. I think this group was revolutionary and much needed.” — Participant 2

“All churches should do this. I would want to lead this in the future.” — Participant 3

“If it weren’t for this group each week [given a crisis experienced mid-group], I don’t think I would still be here.” — Participant 4

Why It Matters

This pilot was small, but the results are promising: when spiritually integrative therapists and spiritual care practitioners, like spiritual directors, pastoral counselors, and chaplains, partner, Christians with trauma can find measurable holistic healing — mentally, emotionally, relationally, and spiritually.

At this point, we have partnered with Fuller, Vanguard, and Journeys Counseling Ministry to expand this study with more groups, so we can confirm these outcomes and trends while learning even more about how spiritually integrative therapy alongside spiritually directive practices like inner healing prayer can support trauma recovery.

Join Us in the Journey

At Integrate You, we believe healing isn’t just about surviving — it’s about being restored, made whole, and reconnected with God and others.

This fall 2025 and January 2026, we’re offering our next group in partnership with Journeys Counseling Ministry, open to enrolled Christian college and university students across California.

Our hope is to begin this next group in October, once all eligible participants are identified.

👉 If you’re a college student — or know someone who is — who’s ready to step into healing, click here to learn more and sign up.

Because trauma doesn’t get the final word. Healing does.